General Court issues second decision in long-running design dispute

Par Richard Milchior, le 9 mai 2022

Article publié dans World Trademark Review

– These invalidity proceedings involving rival furniture companies started in 2016, and went all the way to the CJEU

– In this second decision, the General Court confirmed that the earlier design had been disclosed

– It also confirmed that the contested design lacked individual character

On 2 March 2022 the General Court (Fifth Chamber) issued its decision in Fabryki Mebli “Forte” SA v European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) (Case T‑1/21), which involved a registered Community design representing an item of furniture.

Background

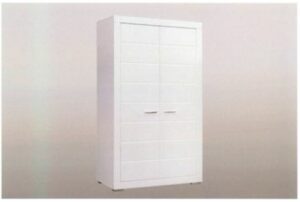

On 17 September 2013 Fabryki Mebli “Forte” SA filed an application for the registration of a Community design for “furniture”:

It was registered as Community design No 001384002-0034.

On 14 March 2016 the intervener, Bog-Fran sp, filed an application for a declaration of invalidity on the basis of Article 25(1)(b) of Regulation 6/2002, claiming that the design was not new and lacked individual character. It filed several documents to support its claims, including:

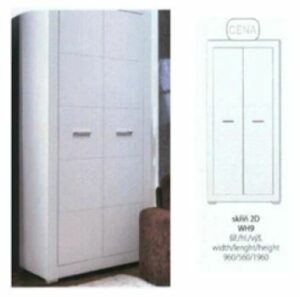

– an extract from a catalogue entitled “NABYTKU – Novinka 2008 – WHITE” containing the following representations of an item of furniture named ‘skrin 2D WH9’ to which the earlier design had been applied:

– an invoice, in Czech, dated 14 August 2008 relating to the printing of 25 000 copies of this catalogue; and

– three invoices, dated 14 August, 4 November and 28 November 2008, respectively, relating to sales of furniture to A JE TO CZ, with confirmation of the receipt of the goods referred to.

The Invalidity Division of the EUIPO upheld the application for a declaration of invalidity. This decision was annulled by the Third Board of Appeal of EUIPO on 14 January 2019 on the ground that the earlier design had not been made available to the public.

On 14 March 2019 the intervener challenged this decision and by judgment of 27 February 2020, Bog-Fran v EUIPO (Case T‑159/19) (‘the annulling judgment’), the General Court annulled the decision of the Board of Appeal on the ground that the board had wrongly considered that the intervener had not demonstrated disclosure of the earlier design. The evidence produced before it proved events constituting disclosure of that design.

On 28 April 2020 Forte (‘the applicant’) brought an appeal against the annulling judgment. By order of 16 July 2020 in Case C‑183/20 P, the Court of Justice of the European Union did not allow the appeal to proceed and the case was remitted to the Third Board of Appeal.

By decision of 28 October 2020, the appeal against the decision of the Cancellation Division was dismissed. In particular, as regards the disclosure to the public of the earlier design within the meaning of Article 7(1) of Regulation 6/2002, the Board of Appeal found that the applicant had not established to the requisite legal standard that the events constituting disclosure could not reasonably have become known to the circles specialised in the sector concerned, and concluded that the earlier design had been made available to the public and that the individual character of the contested design was lacking. In that regard, it first recalled that the designs at issue represented wardrobes and that, in that area, the designer’s degree of freedom was not limited. Second, the informed user, as a result of their interest in furniture, showed a relatively high degree of attention. Third, after examining the designs at issue, it found that there were minor differences which were not sufficient to produce different overall impressions on the informed user.

Decision

The applicant raised two pleas in law, alleging infringement of Articles 7(1) and 6(1)(b) of Regulation 6/2002, in that the Board of Appeal had wrongly concluded that the contested design lacked individual character.

First plea

In support of its first plea in law, the applicant raised three complaints:

1. wrongly finding that the intervener had established the events constituting disclosure of the earlier design;

2. incorrectly dividing the burden of proving knowledge of that disclosure by the specialist circles in the sector concerned; and

3. holding that those circles could reasonably have had knowledge of the disclosure of the earlier design.

First complaint

Article 7(1) of Regulation 6/2002 provides that a design is to be deemed to have been made available to the public if it has been published following registration or otherwise, or exhibited, used in trade or otherwise disclosed, before the date of filing of the application for registration, except where these events could not reasonably have become known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector concerned operating within the European Union, except if the disclosure was made under explicit or implicit conditions of confidentiality.

The applicant submitted that the Board of Appeal had wrongly found that the intervener had proved the veracity of the events constituting disclosure of the earlier design; it disputed the reliability and authenticity of the evidence produced in support of the application for a declaration of invalidity. In the course of the proceedings before the EUIPO, it had claimed that such evidence consisted of copies originating solely from the intervener and not from an “impartial and objective source”. It also challenged the manner in which those documents came into being, and added that no indication was provided as to the addressee of the catalogue in question, either as to the date on which that catalogue was prepared or as to the persons to whom it was submitted. It further mentioned that the invoices confirming the receipt of the goods bore no legible signatures, and the circumstance that the addressee of those invoices was presented as a wholesaler of the intervener cast doubt on the fact that the sales evidenced by those invoices were a commercial transaction which had the effect of making the earlier design public.

It also disputed the authenticity of the invoice dated 14 August 2008 relating to the printing of the catalogue on the ground that the mention of the place at which the printing house was seated was incorrect.

The admissibility of that complaint was disputed on the ground that the court had already ruled, in the annulling judgment, on the probative value of the evidence of disclosure of the earlier design, and that the existence of acts of disclosure of that design comes under the force of res judicata attaching to that judgment. The admissibility of the rest of the applicant’s arguments put forward in the course of the proceedings was disputed on the ground that they were out of time.

The court noted that the annulling judgment became final after the rejection of the leave to appeal by order of 16 July 2020. It recalled, first, that res judicata extended only to the matters of fact and law actually or necessarily settled by the judicial decision in question and, secondly, that the force of res judicata attached not only to the operative part of that decision, but also to the ratio decidendi of that decision, which was inseparable from it. A judgment with relative force of res judicata is invested with absolute effect and, consequently, prevents legal questions which it had already settled from being re-examined.

In order to establish disclosure of the earlier design, the intervener had produced some evidence but, in its decision of 14 January 2019, the Third Board of Appeal had found that the intervener had not established that the earlier design had been made available to the public. This decision was annulled for the following reasons.

First, as regards the authenticity of the evidence, the court found that the existence of the catalogue, of the printing in 2008 of 25 000 copies of the same catalogue and of the sale of furniture, dated 14 August 2008, to which the earlier design had been applied, had been established. Second, the court found that those elements established the veracity of events constituting disclosure of the earlier design. It then considered that, on account of that proof, it was for the Board of Appeal to presume disclosure of the earlier design, before, if appropriate, examining the intervener’s arguments alleging that the events constituting the disclosure in question were not known to the circles specialised in the sector concerned. Therefore, those findings were covered by the force of res judicata attaching to that judgment.

The Board of Appeal had endorsed the reasoning followed by the court in the annulling judgment by taking the view that the disclosure of the earlier design had to be regarded as proved and that, therefore, it was called upon, first, to adopt a position on the applicant’s arguments relating to the question of whether the circumstances of the present case could reasonably prevent those events from becoming known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector concerned and, secondly, to compare the designs at issue in order to assess the novelty and individual character of the design.

Nevertheless, the applicant disputed once again the probative value of the documents produced by the intervener, thereby asking the court to disregard its own findings; however, these were covered by the force of res judicata attaching to its previous judgment. Further, the applicant’s allegations were based on evidence produced for the first time before the court and were thus inadmissible.

Owing to the force of res judicata attaching to the annulling judgment, the first complaint was declared inadmissible.

Second complaint

The applicant criticised the Board of Appeal’s finding that the earlier design had been disclosed.

A design is deemed to have been made available once the party asserting it has proved the events constituting the disclosure. To rebut that presumption, the party challenging the disclosure must establish that the circumstances of the case could reasonably prevent those facts from becoming known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector concerned.

The Board of Appeal had found that it was for the applicant to establish that the circumstances of the case reasonably prevented such events from becoming known to the circles specialised in the sector concerned in the normal course of business.

Therefore, the applicant was wrong to criticise the board for having disregarded the division of the evidential burden of disclosure of the earlier design, with the result that the second complaint was rejected.

Third complaint

The applicant criticised the Board of Appeal for having found that it had not established that the circumstances of the present case could reasonably prevent those disclosure events of the earlier design established by the intervener from becoming known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector concerned.

In order to rebut the presumption that a design is deemed to have been made available once the party relying thereon has proven the events constituting disclosure, it is for the party challenging disclosure to establish that the circumstances of the case could reasonably prevent those facts from becoming known to the circles specialised in the sector concerned in the normal course of business.

In that regard, it must be examined whether it was not actually possible for the circles specialised in the sector concerned to be aware of the events constituting disclosure, whilst bearing in mind what can reasonably be required of them in terms of being aware of prior art. An unregistered design may reasonably have become known if images of that design were distributed to traders operating in that sector. The disclosure to a single business entity or dealer of an earlier design may accordingly, in certain circumstances, be considered as a relevant disclosure. Further, the first sentence of Article 7(1) of Regulation 6/2002 makes the question of whether there is disclosure to the public dependent only upon how that disclosure is in fact achieved.

In the present case, the applicant based its argument on, first, a furniture assembly leaflet bearing the reference ‘WHITE WH9’ to which the earlier design was applied and, second, a written statement dated 18 October 2016 from one of the applicant’s employees claiming to have designed a series of furniture which includes the furniture to which the contested design was applied.

The Board of Appeal did not expressly refer to the evidence described above and, further, the allegations of distortion and misrepresentation of that evidence by the board were not substantiated in any way and were to be rejected. In addition, the absence of an express reference to those items could not in itself lead to the conclusion that the board failed to take them into consideration.

Moreover, as regards, first, the fact that the furniture to which the earlier design was applied was sold disassembled, it was sufficient to note that it had no bearing on the disclosure of that design. As regards, second, the written statement of the applicant’s employee, it was recalled that, in order to assess the evidential value of a document, it is necessary to check the plausibility and the accuracy of the information contained in that document.

One must take account of, among other things, the origin of the document, the circumstances in which it came into being, the person to whom it was addressed and whether, on its face, the document appears to be sound and reliable. The particulars in an affidavit made by a person linked, in any manner whatsoever, to the company relying on it must, in any event, be supported by other evidence; this was not done here.

Consequently, the Board of Appeal was right to conclude that the earlier design had been disclosed and the third complaint was rejected.

Second plea

By its second plea, the applicant criticised the Board of Appeal for having found that the contested design lacked individual character. A registered Community design is considered to have individual character if the overall impression it produces on the informed user differs from the overall impression produced on such a user by any design which has been made available to the public before the date of filing the application for registration or, if a priority is claimed, before the date of priority.

The assessment of the individual character of a Community design is based on a four-step examination, which consists in deciding upon:

1. the sector to which the products in which the design is intended to be incorporated or to which it is intended to be applied belong;

2. the informed user of those products in accordance with their purpose and, with reference to that informed user, the degree of awareness of the prior art and the level of attention to the similarities and the differences in the comparison of the designs;

3. the designer’s degree of freedom in developing the design, the influence of which on individual character is in inverse proportion; and

4. taking that degree of freedom into account, the outcome of the comparison, direct if possible, of the overall impressions produced on the informed user by the contested design and by any earlier design which has been made available to the public, taken individually.

The individual character of a design thus results from an overall impression of difference or lack of ‘déjà vu’, from the point of view of an informed user, in relation to any previous presence in the design corpus, without taking account of any differences that are insufficiently significant to affect that overall impression, even though they may be more than insignificant details, but taking account of differences that are sufficiently marked so as to produce dissimilar overall impressions.

In the light of those principles, the court examined whether the Board of Appeal had correctly concluded that the contested design lacked individual character.

The designs at issue represented wardrobes. The informed user of a wardrobe could be anyone who purchases such a product, uses it in accordance with its intended purpose and has become informed on the subject by browsing through catalogues of, or including, furniture, visiting the relevant stores or downloading information from the Internet and, as a result of their interest in the products concerned, shows a relatively high degree of attention when using them. The court also noted that the freedom of the designer of wardrobes was not limited, in particular as regards the choice of size, material, supporting elements, colour and decorative patterns. It also found that the images of the earlier design were of sufficient quality for comparing the overall impressions produced on the informed user by the designs at issue. In the context of that comparison, it noted that the designs at issue coincided in their white rectangular shape, their broad frame, their doors divided into small sections by several parallel thin horizontal lines and a longer thin vertical line, as well as by their feet of the same size and shape. The furniture also differed in the number of horizontal lines and, therefore, of sections on their doors, as well as in the exact shape of those sections, which are rectangular in the contested design and square in the earlier design, and, lastly, in the exact position of the handles of their doors.

The Board of Appeal had taken the view that the feature that first attracted the informed user’s attention was the division of the front part of the wardrobe into two doors of similar proportions, each divided into several sections by fine horizontal lines. It added that the designs at issue would both be perceived as representing a wardrobe with two doors containing small sections that differ only in minor details, namely the exact shape and number of sections and the position of handles. It inferred that those slight differences would be perceived as minor variations of one and the same design and could not suffice to produce a different overall impression.

As regards the quality of the images of the earlier design and the fact that certain parts of the furniture in question are not visible, it stated that those representations enabled to note the similarities and differences between the designs. Moreover, the case law had already considered that part of the product represented by a design which is outside the user’s immediate field of vision will not have any major impact on their perception of the design, and the overall impression produced by a design must necessarily be determined in the light of the manner in which the product in question is used, in particular on the basis of the handling to which it is normally subject on that occasion.

In this case, the designs at issue represented wardrobes, which are most often handled by opening their doors and are intended to be placed on the ground and against a wall. Therefore, their rear, lower and upper surfaces will be, at the very least, not very visible, and are liable to have little influence on the overall impression produced on the informed user.

As regards the argument that the designs at issue, due to their differences, produced different overall impressions on the informed user, the court recalled that differences will be insignificant in the overall impression produced by the designs at issue where they are not sufficiently pronounced to distinguish the goods in question in the perception of the informed user or offset the similarities found between those designs.

In that regard, the greater the designer’s freedom in developing a design, the less likely it is that minor differences between the designs at issue will be sufficient to produce different overall impressions on an informed user. In the present case, the court noted that the designs coincided in their rectangular shape and their white colour. The applicant claimed that the furniture to which the earlier design was applied was white in one of the representations and ‘greyish’ in the other. Apart from the fact that that difference in colour could result from the lighting conditions of the wardrobe represented, the court held that, even if that claim were proved, that difference is so slight as not to be able to influence in a decisive manner the overall impression produced by that design.

Secondly, the applicant merely relied on the Board of Appeal’s assertion that the informed user would not overlook the differences between the designs in order to infer that those designs produced different overall impressions on that user.

However, the informed user would perceive the differences between the designs in question as minor. Therefore, having regard to the high degree of freedom of the wardrobe designer, these could not lead to those designs producing different overall impressions on that user.

Therefore, the Board of Appeal had concluded correctly that the contested design lacked individual character. The second plea in law was rejected and the action dismissed in its entirety.

This article first appeared on WTR Daily, part of World Trademark Review, in February 2022. For further information, please go to www.worldtrademarkreview.com.