General Court: Board of Appeal erred in finding that handle design lacked individual character

Par Richard Milchior

Article publié dans World Trademark Review

– The Board of Appeal found that the contested design did not produce a different overall impression on the informed user as that produced by an earlier design

– The court found that the rounded curvature of the edges of the contested design was accompanied by a thinner and smoother appearance which the informed user would easily notice

– The differences in the angles of the grip and the neck were neither marginal nor minor variations of one and the same design

On 10 April 2024 the General Court issued its decision in M&T 1997 as v European Union Intellectual PropertyOffice (EUIPO) (Case T‑654/22), which concerned a registered Community design (RCD) representing door and window handles.

Background

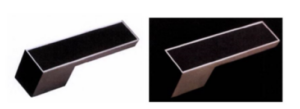

On 23 October 2020 VDS Czmyr Kowalik sp k filed an application for a declaration of invalidity of the RCD depicted belowfollowing an application filed by the predecessor in title of M&T on 17 November 2012:

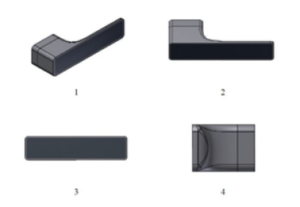

VDS claimed that the contested design had no individual character because the overall impression produced on the informed userdid not differ from the impression produced by the shape of handles existing on the market prior to its filing date. VDS relied on theearlier Griffwerk FRAME design, represented below:

The Cancellation Division of the EUIPO upheld the application for a declaration of invalidity, and the Board of Appeal dismissed theappeal.

General Court decision

M&T appealed, relying on two pleas in law.

The first plea was divided in three parts. M&T complained that the Board of Appeal had erred in finding that the overall impressionproduced by the contested design on the informed user did not differ from that produced by the earlier design on that user and that,therefore, the contested design did not have individual character.

Individual character must be assessed in the light of the overall impression that it produces on the informed user. In the case of aRCD, the overall impression produced on the informed user must be different from that produced by any design made available tothe public before the date on which the application for registration was filed or, if a priority is claimed, the date of priority.

The assessment of the individual character is carried out in four stages:

1. the sector to which the products in which the design is intended to be incorporated or to which it is intended to be appliedbelong;

2. the informed user of those products in accordance with their purpose and, with reference to that informed user, the degreeof awareness of the prior art and the level of attention to the similarities and the differences in the comparison of thedesigns;

3. the designer’s degree of freedom in developing the design, the influence of which on individual character is in inverseproportion; and

4. taking that degree of freedom into account, the outcome of the comparison, direct if possible, of the overall impressionsproduced on the informed user by the contested design and by any earlier design which has been made available to thepublic, taken individually.

The concept of ‘informed user’ lies somewhere between that of the ‘average consumer’, applicable in trademark matters, who neednot have any specific knowledge and who, as a rule, makes no direct comparison between the trademarks at issue, and the ‘sectoralexpert’, who is an expert with detailed technical expertise. It thus refers to a particularly observant user, either because of theirpersonal experience or their extensive knowledge of the sector in question.

As regards the informed user’s level of attention, the qualifier ‘informed’ suggests that the user knows the various designs existingin the sector concerned, possesses a certain degree of knowledge with regard to the features which those designs normally include,and, as a result, shows a relatively high degree of attention when he/she uses the products.

The concept of ‘informed user’ does not refer to a professional quality linked to the product concerned and, in this case, did not referto the handle salesperson. The case law cited by M&T could not call that finding into question and the complaint that the board hadmade an error of assessment in its definition of the ‘informed user’ was rejected.

The board had found that the degree of freedom of the designer of door handles was high. According to the case law, the degree offreedom of the designer of a design is determined by, among other things, the constraints of the features imposed by the technicalfunction of the product or an element thereof, or by statutory requirements applicable to the product to which the design is applied.Those constraints result in a standardisation of certain features, which will thus be common to the designs applied to the productconcerned.

In the present case, the board’s assessment was consistent with the case law according to which the degree of freedom of thedesigner of a door handle with a grip is high. M&T’s complaint that the board had erred in its assessment of the degree of freedomof the designer was rejected.

The board had also found that the contested design did not produce a different overall impression from that of the earlier design.First, it noted that the two designs at issue showed a door handle consisting of a lever in a flat, rectangular shape, a grip in a cuboidshape of the same dimensions and proportions, and a thin profile. Second, it noted that the differences between the two designswere limited only to the curvature of the edges, which were rounded in respect of the contested design, and to the shape of theneck, the transition of which was curved in the contested design and perpendicular in the earlier design, and that those differenceswere not sufficient to produce distinct overall impressions on the informed user, in particular in view of the designer’s high degree offreedom. The difference in curvature would not be immediately perceived by the informed user without an examination of the exactdegree of angles. Further, the difference in the neck, which is located at the back of the handle, did not play a decisive role in theoverall impression. Third, the board had rejected two other differences relied on by M&T, namely a rosette shape and a shade ofcolour on the contested design, finding that the existence of the former could not be inferred from the lines of the contested designand that the second was not sufficient to offset the similarities of the designs. Fourth, it found that the fact that the contesteddesign obtained the Red Dot award in 2013 was irrelevant.

M&T submitted that there were numerous differences between the designs at issue. Insofar as the informed user has an increasedlevel of attention, they would easily be able to perceive the distinctive design of the back of the door handle, even when looking at itfrom the front and, consequently, their overhead view of the handle. In that regard, M&T submitted at the hearing that the roundedand softened edges of the handle were not only visible, but also tangible for the end user.

According to settled case law, the individual character of a design results from an overall impression of difference from the point ofview of an informed user in relation to any previous presence in the design corpus, without taking account of any differences thatare insufficiently significant to affect that overall impression. The comparison of the overall impressions produced by the designs atissue must be synthetic and not limited to an analytic comparison of similarities and differences, and the overall impressionproduced on the informed user by a design must be determined in the light of the manner in which the product is normally used.Account must be taken of the fact that the attention of the informed user is focused rather on the most visible and most importantelements when using the product.

The court noted that, when the informed user uses a door handle with a grip in accordance with its normal use, he/she clasps itsgripping area with the hand to exert downward pressure so that the latch of the door slides and allows the door to be opened.Where the informed user approaches the door handle, he/she sees it from above. Accordingly, the most visible elements of thehandle are those corresponding to the outward-facing parts of the handle, namely the front, side and top parts of the handle. Thedifferences at the back, namely the curvature of the edges and the shape of the neck, will also be visible to the informed user andwill not be overlooked. Here, the rounded curvature of the edges of the contested design was accompanied by a thinner andsmoother appearance which the informed user would easily notice.

Therefore, the rounded and thinner shapes of the edges of the contested design constituted differences with the earlier designwhich would be perceived by the informed user as influencing the manipulation of the handle and were important elements inrelation to the overall impression produced by the contested design. Those aspects had an impact on the ease of use of the handle,since they corresponded to the parts of it which came into direct contact with the hand of the informed user.

Consequently, the attention of the informed user would be focused on all the elements set out above, and the court held that thedifferences in the angles of the grip and the neck were neither marginal nor minor variations of one and the same design. A morerounded shape generally results in a softening of the lines of the neck and grip, which has a significant effect both on the overallappearance and on the ease of use of the door handle. It was therefore an element which attracted the informed user’s attention.

It followed that, although the designer’s freedom was high, those differences were sufficiently significant to produce a differentoverall impression. The board’s decision was thus annulled.

This article first appeared on WTR Daily, part of World Trademark Review, in May 2024. For further information, please go to www.worldtrademarkreview.com.